|

Post by Summer Scholar Lily Pare Hall-Butcher It’s 1860 and the Crown has just declared war on its Māori subjects in the province of Taranaki, Aotearoa New Zealand. In response, thousands of men from throughout the British Empire come to New Zealand as soldiers of the British Imperial Army. Over the next few years the Army fights battles all over the North Island and bolsters the white settler presence in the South Island. While the majority of these men leave Aotearoa with their regiments, others are officially discharged and stay as settlers. Yet another group left their regiments unofficially – the deserters. Elusive in the archives as they often were in life, most simply disappear from the records. Some became infamous, while others rose to positions of prominence in settler society. Desertion from the military was a serious crime in the nineteenth century, which could be punished with imprisonment or branding on the skin.[1] So naturally the last thing any deserter wanted was to be found under his real name by the authorities. This makes tracking men through the archives difficult. Out of the over 800 men who deserted the British Army while stationed in New Zealand, sixty-six men were selected for further research.[2] Of the sixty-six men researched for this project, under half had any information about them in the archives after they deserted. Changing their names to avoid detection was one tactic used by deserters. Samuel Lupton of the 65th regiment went by the name Leonard Clare after deserting the British Army on 15 June 1865 at Te Awamutu.[3] Lupton developed an elaborate story to go with the alias. The New Zealand Herald reported: “He says his name is Leonard Clare, that he is a native of Queen's County, Ireland and that he came to Auckland in the ship Bombay. He says he is a tailor by trade and that he has been up the country as far as Drury."[4] In fact, he was a former sailor from Durham, England.[5] The New Zealand Herald it seems, was suspicious of his claims, noting “[a]lthough a tailor, he has never asked anyone in Auckland for work. He declined to mention the names of any of the passengers of the ship Bombay.”[6] So too were the police: "The police...say they know his face. They disbelieve his story about coming in the Bombay. He certainly has nothing of the softness of the "new chum." He has what the late Sergeant Mirehouse used to call the "philosophy of crime" at his fingers' end."[7] Unfortunately for him, his pseudonym wasn’t any help when he was recognised in court by a sergeant from his regiment after attempting to steal some gold pins from a shop window display in Queen Street on 21 June 1865.[8] Deserters frequently committed crimes. Of the 31 men where some trace exists in the archives, 17 left some indication of their lives beyond the army. Of these 17 men, eight had been accused of or charged with a crime besides desertion. Michael Hemsley of the 65th regiment was the most violent criminal of the researched men. He committed armed robbery against fellow soldiers, settlers and even a prison guard.[9] He attempted to escape prison three times and succeeded once.[10] Theft and drunkenness were recurring offences of which deserters were accused, to the point some deserters are traceable wholly through the reports of their trials at the police court or supreme court in the newspapers. William Candy of the 40th regiment is one such deserter. On 12 April 1860, before coming to New Zealand, Candy was accused of stealing a watch belonging to Robert Owens in Melbourne, Australia.[11] He was later charged with stealing a purse containing five pounds from Robert H. McRae on 12 March 1863 in Auckland.[12] He escaped from prison with a man called William James on the night of 15 – 16 July 1863 by hiding in “the place used for storing coal”.[13] After the final departure of the last British troops in 1870, Candy appears twice more in the newspapers. In June 1876 he was charged with “attempting to rescue a prisoner from legal custody” after trying to intervene when his friend Alexander Beain, a sailor, was arrested.[14] Beain was discharged and “advised to keep better company.”[15] The last trace of William Candy in the archives is in June 1876 when he was actually the victim of crime after another man stole his clothes.[16] Men like Samuel Lupton, Michael Hemsley and William Candy conform to some contemporary perceptions of the disreputableness of army life. Many believed that men who joined the army – notorious for its bad conditions, harsh discipline and poor pay – were dishonest characters attracted by the opportunity to run away from responsibility, as well as the rum ration.[17]

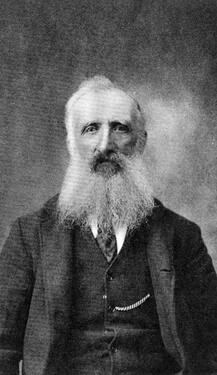

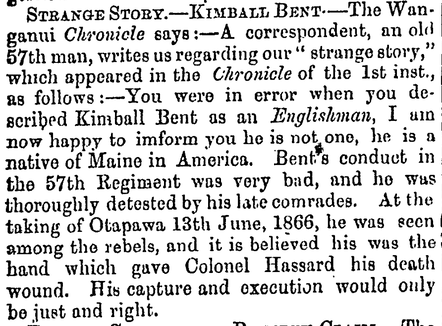

Māori memories and perceptions of men like Bent are difficult to find in the existing scholarship on desertion in New Zealand. However, the events of his life suggest he had a more complex relationship with the Māori communities he lived in than simply that of a captor. He was married at least twice during his time in Taranaki, under different circumstances.[21] After his capture in 1865, he was “forcibly married” to Te Rawanga, a Ngati Ruanui woman.[22] Later in 1866, he was married to Rihi or Te Hau-raro-i-ua, the daughter of the Taiporohenui rangatira Rupe after he had helped cure Rupe’s son of a “serious illness.”[23] He lived with Rihi for three years, fathering a child who later died.[24] Even after Rihi’s death, he remained with her people for at least a decade, long after the end of the wars and the cancellation of bounties for deserters.[25] He also seems to have continued to perform special tasks for her community. A newspaper report from 1886 describes him “baking and decorating six large cakes and sixty smaller ones” for the opening of a meeting house at Hokorima near Hawera.[26] Bent was interviewed about his experiences later in life by the historian James Cowan, who published his account as a book, The Adventures of Kimble Bent in 1911, thus the narrative of the “notorious” Kimball Bent is possibly the best remembered example of desertion during the New Zealand Wars.[27] When he died in 1916, numerous obituaries described his “remarkable career.”[28] Yet a life of exile or crime was not the only fate of men who deserted the British Army in the nineteenth century. Harder to find in the archives but probably numerous among the unrecorded men are those who slipped into colonial society and became respectable citizens. George Hill Boggs of the 40th regiment deserted from the British Army on 15 April 1866. He disappears from the archives for over a decade before resurfacing in 1879 as a witness at a theft trial.[29] He was not accused himself, but rather had become established as the proprietor of the Waverley Hotel in Taradale, Napier.[30] In the intervening decade he had not only become a businessman but had also married Isabella Murray and become the father of three sons.[31] An active member of the local Quadrille Club, he offered free strawberries and cream to visitors at his hotel on Sundays.[32] Perhaps it is not surprising that after he died on 10 August 1881, the Hawke’s Bay Daily Telegraph mourned his death in the following terms: "[w]e regret to learn that Mr Boggs, of the Waverley Hotel, Taradale died somewhat suddenly yesterday. It appears that he had not been in good health for some time, and his illness develoyed [sic] into serous [sic] apoplexy [cerebral haemorrhage]. Drs. Caro and Spencer were in attendance, but their services were too late to be of any avail."[33] His wife continued to be an important member of their community until her death in 1924, when she was memorialised in an obituary in the Waiapu Church Gazette.[34] Settling in a colony “where at least there was a chance of owning land, an impossible dream in Britain” for working class men, was a strong motivation for deserting.[35] The 40th regiment had been due to leave New Zealand in 1866, making it possible that George Hill Boggs deserted so that he could take advantage of the opportunities for a Pakeha man in colonial society to own land or establish a business which he later did.[36]

By 3 July 1865, he was trusted to represent the imperial forces at a dinner celebrating the opening of the Alexandra Hotel, Te Awamutu. The New Zealander reported; "[a]fter appropriate toasts and speeches, Mr. Charles Montrose, the only member of the Imperial service present, responded to a toast in a trite and soldierlike manner. The party did not separate until an early hour on the morning of Tuesday, and the gallant host (who is an ex-sergeant of militia) was as well satisfied with his guests as they were with his liberality, affability and kindness." [39] Montrose’s transformation into respectable citizen continued apace. Around 1867, he began working for the Daily Southern Cross, the start of a career in journalism that was to last for more than thirty years.[40] He worked as an editor on many papers including the Auckland Star, Waikato Times, Wellington Times and The Observer.[41] He worked for a number of telegram agencies throughout the 1870s-1880s, and as a journalist in Australia, authored two books and wrote a play.[42] Montrose married and divorced a woman named Matilda and fathered at least three children, one of whom died at a young age.[43] Between 1892-1893 he did something most extraordinary for a man who had deserted the army: he toured New Zealand giving lectures on his experience of the New Zealand Wars. Retracing the path he had taken thirty years earlier as a member of the invading British army, he toured Te Awamutu, New Plymouth, Hawera, Onehunga and Thames.[44] On three occasions his lectures were given piano accompaniment by Australian pianist Alice Sydney Burvett.[45] In stage performances complete with light and musical effects that were designed to dazzle, he helped to build an origin story for a settler audience hungry for history that would authenticate their settlements. Charles Otho Montrose built his reputation and in turn, his career from his service in the British Imperial Army. When he died in 1907 there was a conscious double meaning to the headline “death of a veteran journalist.”[46] Notes

[1] Tim Ryan, ‘The British Army in Taranaki’ in Kelvin Day (ed.) Contested Ground Te Whenua I Tohea – The Taranaki Wars 1860-1881 (Wellington: Huia Publishers, 2010), pp.133-134 [2] Soldiers of Empire deserters database. Figure excludes 70th regiment. [3] ‘Untitled’, New Zealand Herald, 24 June 1865 p.5 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH18650624.2.15 (accessed 23 Nov 2018) [4] ‘Daring attempt at robbery’ New Zealand Herald, 22 June 1865 p.4 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH18650622.2.16 (accessed 23 Nov 2018) [5] WO 12 Muster Rolls [6] Ibid [7] Ibid [8] Ibid [9] ‘Supreme Court’ New Zealander 9 December 1864 p.5 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZ18641209.2.26 (accessed 27 Nov 2018); ‘Military Movements’ Daily Southern Cross 9 May 1863 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DSC18630509.2.13 (accessed 27 Nov 2018); ‘Sydney. (From our own correspondent.) May 25, 1863. Supreme Court.—Thursday. (Before his Honor Sir George A Arney, Chief Justice)’ Daily Southern Cross 5 June 1863, p.3 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DSC18630605.2.19 (accessed 27 Nov. 2018); ‘Supreme Court’ New Zealander 9 December 1864 p.5 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZ18641209.2.26 (accessed 27 Nov 2018) [10] ‘Monday, September 12’ Daily Southern Cross 12 September 1864, p.4 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DSC18640912.2.12 (accessed 27 Nov. 2018); ‘Provincial Council Papers’ Daily Southern Cross, 21 November 1866, p.5 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DSC18661121.2.19 (accessed 27 Nov. 2018) [11] ‘Police – City Council’ The Melbourne Argus 6 June 1860 p.6 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5683798 (accessed 11 Dec 2018) [12] ‘Police Court – Saturday’ New Zealander, 23 March 1863, p.3 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZ18630323.2.18 (accessed 11 Dec 2018) [13] ‘Thursday, July 16 1863’ Daily Southern Cross, 16 July 1863, p.3 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DSC18630716.2.10 (accessed 11 Dec 2018) [14] ‘City Police Court’ Otago Daily Times 3 June 1876, p.3 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ODT18760603.2.22 (accessed 11 Dec 2018) [15] Ibid [16] ‘Law and Police’ New Zealand Herald 4 July 1876, p.6 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH18760704.2.24.10 (accessed 11 Dec 2018) [17] Peter Burroughs, ‘An Unreformed Army? 1815-1868’ in David Chandler and Ian Becketts (eds) The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army (Oxford: Oxford University Press: 1994), p.168; Ryan, ‘The British Army in Taranaki’, p.131 [18]W. H. Oliver, ‘Story: Bent. Kimble’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, (1990) now hosted on Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand; https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1b19/bent-kimble (accessed 3 Jan 2019) [19] Ibid [20] ‘Strange Story – Kimball Bent’ Wellington Independent, 12 September 1868, p.4 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/WI18680912.2.13 [21] Ibid [22] Ibid [23] Ibid [24] Ibid [25] Ibid [26] Ibid [27] Damon Ieremia Salesa, Racial Crossings: Race, Intermarriage, and the Victorian British Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010) p.197 [28] ‘A remarkable career’ Taranaki Daily News, 15 June 1916, p.3 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TDN19160615.2.16 (accessed 22 Jan 2019) [29] ‘Resident Magistrate’s Court’ Hawke’s Bay Herald, 22 May 1879, p.3 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/HBH18790522.2.13.3 (accessed 17 Dec 2018) [30] Ibid [31] Sandra Allan, ‘George Hill Boggs’ Find A Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/188065757/george-hill-boggs (accessed 19 Dec 2018) [32] ‘Dancing’, Hawke’s Bay Herald, 17 May 1880, p.3 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/HBH18800517.2.14.2 (accessed 13 Dec 2018); ‘Wanted known’ Hawke’s Bay Herald, 22 November 1879, p.1 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/HBH18791122.2.2.8 (accessed 13 Dec 2018) [33] ‘Untitled’, Daily Telegraph, 11 August 1881, p.2 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DTN18810811.2.11 (accessed 13 Dec 2018) [34] Isabella Boggs remarried after the death of George Hill Boggs and thus her obituary is under the name Isabella Bicknell: ‘Parish Notes’, Waiapu Church Gazette, 1 May 1924, p.9 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/WCHG19240501.2.16 (accessed 2 Jan 2019) [35] Ryan, pp. 133-134 [36] Ian Wards, ‘British Army in New Zealand’ in Ian McGibbon (ed.) The Oxford Companion to New Zealand Military History (Auckland: Oxford University Press, 2000) p.70 [37] 'Police Court – Yesterday’ New Zealander, 8 January 1863, p.3 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZ18630108.2.14 (accessed 29 Nov 2018 [38] Ibid [39] 'Untitled' New Zealander, 17 July 1865, p.2 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZ18650717.2.9 (accessed 29 Nov. 2018) [40] 'Pars About People', Observer 17 August 1907, p.4 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TO19070817.2.7 (accessed 20 Dec 2018) [41] 'Lecture by Mr C.O. Montrose’ Taranaki Herald, 12 July 1892, p.2 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TH18920712.2.17 (accessed 20 Dec 2018) [42]'Pars About People', Observer 17 August 1907, p.4 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TO19070817.2.7 (accessed 20 Dec 2018); 'Greville's Telegram Company (Reuter's Agents)' Evening Star 5 September 1870, p. 2 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ESD18701105.2.14.1 (accessed 20 Dec 2018); 'Pars About People', Observer 17 August 1907, p.4 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TO19070817.2.7 (accessed 20 Dec 2018); ‘Supreme Court. In Bankruptcy. This day’ Evening Post, 3 December 1873, p.2 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP18731203.2.9 (accessed 20 Dec 2018); 'Called Back’, Auckland Star, 15 December 1884, p.2 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS18841215.2.23 (accessed 20 Dec 2018); 'Some more objections’, New Zealand Tablet, 3 November 1882, p.15 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/NZT18821103.2.21 (accessed 2 Jan 2019); Charles O. Montrose, Trades, Unions, Strikes and their Remedies (Melbourne: Victorian Review, 1886) https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/15214102 (accessed 21 Dec 2018); Charles Otho Montrose and the Melbourne 'Argus'', Observer, 14 September 1889, p.17 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TO18890914.2.46.14 (accessed 20 Dec 2018); Untitled' Taranaki Herald, 1 April 1889, p.2 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TH18890401.2.9 (accessed 20 Dec 2018) [43] ‘Auckland’, Wanganui Herald 6 January 1883, p.2 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/WH18830106.2.17.4 (accessed 20 Dec 2018); ‘Death’, New Zealand Herald, 26 November 1881, p.4 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH18811126.2.20 (accessed 20 Dec 2018) [44] 'Daily Memoranda – January 23’ New Zealand Herald, 23 January 1893, p.4 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH18930123.2.13 (accessed 20 Dec 2018); 'Lecture by Mr C. O. Montrose’ Taranaki Herald, 12 July 1892, p.2 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TH18920712.2.17 (accessed 20 Dec 2018); To-night's Concert and Lecture', Hawera & Normanby Star, 24 November 1892, p.2 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/HNS18921124.2.12 (accessed 20 Dec 2018); 'Daily Memoranda – March 30’ New Zealand Herald, 30 March 1893, p.4 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH18930330.2.21 (accessed 20 Dec 2018); 'Miss Alice Sydney Burvett', Thames Star, 18 April 1893, p.2 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/THS18930418.2.17 (accessed 20 Dec 2018); 'You Don't Say So!', Fair Play, 1 June 1894, p.4 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/FP18940601.2.3 (accessed 2 Jan 2019) [45] To-night's Concert and Lecture', Hawera & Normanby Star, 24 November 1892, p.2 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/HNS18921124.2.12 (accessed 20 Dec 2018); 'Daily Memoranda – March 30’ New Zealand Herald, 30 March 1893, p.4 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH18930330.2.21 (accessed 20 Dec 2018); 'Miss Alice Sydney Burvett', Thames Star, 18 April 1893, p.2 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/THS18930418.2.17 (accessed 20 Dec 2018) [46] 'Death of a veteran Journalist’ Otago Witness, 14 August 1907, p.36 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/OW19070814.2.154 (accessed 20 Dec 2018)

7 Comments

25/1/2020 06:21:23 pm

Hi Lily

Reply

Eliza Bradley

12/2/2021 07:35:45 pm

Looking for my great great uncle from Scotland an orphan in 1845-1847 shipped to Tasmania then dragged off the The Crimean War but possibly came back to Tasmania..

Reply

25/1/2020 07:07:18 pm

Hi Lily - while I think of it, although not Deserter related, the following may be of interest to the Project Team.

Reply

Rebecca Lenihan

13/2/2020 11:22:00 am

Hi Ian,

Reply

nancy mclaughlin

15/9/2020 05:18:42 pm

Your notes re the Bradleys are a little faulty. The one who purchased the Charteris Bay property was the Reverend Reginald Robert Bradley. He was a brother of Richard Holland Bradley who married Sophia Harding.

Reply

Daemynn Walker

7/12/2022 09:42:07 pm

Hi, I read this with great interest and wanted to enquire as to the date when the bounties for deserters was cancelled?

Reply

Rebecca Lenihan

9/12/2022 11:17:30 am

Good question! We're not sure. If we find out though, I'll come back here and let you know. If we're both lucky someone else reading this will know and can fill us both in!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

Favicon image: Thomas Matravers album, Sir George Grey Special Collections, 3-137-26d, Auckland Libraries

RSS Feed

RSS Feed