SOLDIERS OF EMPIRE

|

Meena Al-Emleh Sitting in storage in Archives New Zealand’s Wellington collection, alongside numerous seemingly identical materials, is the Treasury Civil Pensions Ledger, 1878-1886. This ledger is part of a wider series of Imperial Pension records, but there is something that makes the Civil Pensions ledger special – it’s entries primarily list Indian servicemen receiving pensions in New Zealand.[1] It is a clear record of the imperial connection between British India and New Zealand, a connection that has been obscured in our own popular remembering.

1 Comment

The year is 1861. In the north, conflict between British-led government forces and Taranaki iwi has taken a brief pause. In April, several Te Ātiawa rangatira agree on terms of peace with the Crown. Wiremu Kingi, a notable exception, declares his consent for the peace but declines to sign and retreats into the Waikato. Grievances over land at Waitara in Taranaki continue to generate tension, the truce is uneasy, and the British military presence in the colony of New Zealand remains substantial.

Over the summer of 2017-18 we were once again very fortunate to be joined by 4 Summer Scholars.

At the Auckland War Memorial Museum Max Nichol was exploring the transformation of Auckland from a town dominated by barracks and the coming and going of military in the early 1860s to a confident colonial port city by the end of the century. The thorough and detailed report of his research findings looks at, among other things, the temperance movement in Auckland, leisure and social lives in Auckland, and the transformation of Albert Barracks to Albert Park. At Puke Ariki Sian Smith worked with amateur photographer and collector William Francis Gordon’s photograph album “Some “Soldiers of the Queen” who served in the Maori wars and other notable persons connected herewith” (PHO2011-1997). A unique historical artefact, the album dates from around 1900 and contains over 450 photographs of soldiers, civilians and Māori involved with the New Zealand Wars. The portraits are loosely ordered into regiments and most are annotated in Gordon’s distinctive handwriting. The album is an integral part of Puke Ariki’s collection of Taranaki Wars material, memorialising those who are depicted and bringing their faces/identities into striking contemporary view/attention. Sian began her project entering the 20% of the album not yet catalogued into Puke Ariki’s collection management system and created networks between images in the album with other items and records in Puki Ariki’s collection. Beyond this useful work that has made the full album more accessible to researchers, Sian developed biographical information for both a selection of people depicted in the album and the regiments mentioned. At Te Papa Caitlin Lynch was also working with photographs compiled by W.F. Gordon, in this case a collection of carte-de-visite photographs acquired by the Dominion Museum in 1916. Caitlin worked to contextualise the photographs by identifying related objects in other collections across Te Papa. Beyond this linking of records/items in the collection, Caitlin meticulously pieced together narratives of specific individuals and battles. You can read about some of her speculations/thoughts/research trails while working on the project on the Te Papa Blogs linked below:

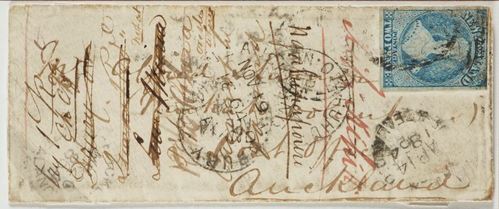

Our internal VUW Summer Scholar was Philip Little, who transcribed and analysed the ‘Effects and Credits’ pages of the WO 12 Muster Roll archives of the 50th, 65th, and 68th regiments in search of answers to such questions as where did they come from, what did they do, how did they live and how did they die. A poster of his findings is available here. Post by Summer Scholar Scott Flutey Over the summer of 2016/17 I worked as a VUW Summer Scholar with the Gerald Ellott philatelic collection at Te Papa (group reference PH859) for the “War by post and bullet” project: transcribing, digitising, and researching items of correspondence relating to Britain’s military presence in New Zealand during the 1860s. The correspondence in the Ellott collection comprises letters between people in private rather than official capacities, thereby providing an important complement to the official record. The project transcriptions and accompanying high-resolution digital photographs of the material are publicly accessible. The Ellott collection contains 343 objects. Of these, 185 objects were digitised and transcribed for this project. These objects involve 141 individuals, who were either senders, recipients or military superiors who authorised correspondence with a signature: often individuals fall into multiple categories across the correspondence. The various postal items which comprise the digitised collection can be grouped into several different categories. 136 are covers (envelopes), eight are entires (letters folded to form an envelope which feature stamps and postal markings on the blank reverse of the letter), and 56 are traditional letters. Most of these items are individual, one-off surviving, pieces of correspondence between senders and recipients. There is also a series of 52 letters from Corporal George Tatler (65th Regiment) to his mother in England spanning the period between 1854 (when Tatler enlisted) and 1865 (when he was discharged from the army). Outside of entire from H.C. Balneavis to Lieut General Wynyard, 6 May 1862. An 'entire' is a letter folded into an envelope that features full, surviving, postage stamps and markings on the back of the letter itself. PH000905, Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa Tongarewa. Covers (envelopes), even without the original letters they enclosed, have great value for historians of the 19th century wars. The markings on the envelopes show us the elaborate network of communication which war spread across the globe and across New Zealand. An integral aspect of the postal system globally was the use of postmarks to signify that a letter had been processed through a receiving post office, any further post offices along the way, and also whether it had travelled by ship (a commonplace practice when rail was still in a state of early development in New Zealand, and roads were dangerous or non-existent). Postmarks thus show the route that a letter took between being sent and received – with exact dates and locations. Redirected mail, or anything that affected the postal process, was also clearly marked by civilian and military postmasters. Military postmasters were soldiers appointed to process mail passing through the various redoubts, military encampments, or even sites of battle. The Ellott collection shows that these temporary post offices were integral to the British communication system during the New Zealand Wars. Overall, the postmarks provide highly valuable evidence of the structure and speed along which communication travelled across the globe in the mid-nineteenth century, providing an insight into the speed and modernity of contemporary networks. This letter, Alfred Harper, a Waikato Volunteer, bears the marks of multiple redirections between 20 March 1864 and 19 November 1864, starting at Auckland then travelling to Otahuhu, Papakura, Kihi kihi, Drury, Lower Wairoa, Queen's Redoubt (Pokeno), Ngahinepouri, and eventually finding the recipient in Auckland. PH000914, Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa Tongarewa Most New Zealand Wars-related material from the Ellott collection was sent during the 1860s, a decade which saw warfare across the North Island. Much of the fighting occurred in Waikato and Taranaki, and the Ellott collection reflects this in terms of content origin. There are many letters from the period 1863-1866. Year No. of objects in collection 1860 9 1861 8 1862 7 1863 18 1864 59 1865 37 1866 22 1867 7 1868 2 1869 5 The Ellott collection holds exceptionally rich and rare material which is useful to researchers in a number of different ways. Data about the nature and specifics of communication can be found in postal markings, while the voices of soldiers and civilians (both Maori and European) and their loved ones make themselves heard very clearly in letters and notes. We had assumed we would probably never know the story behind John Smith’s buttock wound, described in Max’s blog of March 2017, ‘John Smith’ being the archetype of a person you are unlikely to ever be able to find the correct match for in the historical record. However Michael Fitzgerald, one of our advisory board members, happened upon the story while browsing PapersPast recently. It is quite the story, though the motivations of the shooter still remain unclear.

New Zealand Spectator and Cook’s Strait Guardian, 12 October 1864, p.4 |

Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

Banner image: Detail of Breech loading rifle, Snider action, made by the Royal Small Arms Factory, Enfield, England, 1861. Calibre .577, Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa Tongarewa, DM000046

Favicon image: Thomas Matravers album, Sir George Grey Special Collections, 3-137-26d, Auckland Libraries

Favicon image: Thomas Matravers album, Sir George Grey Special Collections, 3-137-26d, Auckland Libraries

Copyright © 2021

RSS Feed

RSS Feed